We are ready to look at the actions

The actions of the [N]:

The text states that the [N] do 3 things, marked by waw-consecutives:

1. They come out (yts’) of the city

2. They scorn (qeles) him [Elisha]

3. They say to him “go up, baldhead’’ twice.

These are stand-alone verbs and not modifiers of one of the others.

In other words, it does NOT say any of these things:

· The come out of the city, scorning him, saying GUBH/GUBH.

· The come out of the city, and scorn him, saying GUBH/GUBH.

· Coming out of the city, they scorn him, saying GUBH/GUBH.

The Waw-Consecutive would be roughly equivalent to “and then they did X”. Sometimes there is not a ‘hard break’ between the actions, but they are still distinct actions/predications from one another.

So, for us, this means:

· The came ‘out of’ the city, and not ‘up from’ the city – i.e. they came from Bethel not Jericho.

· Their ‘scorning’ was distinct from (although clearly reflected in) their SAYING ‘go up, baldy’.

· The ‘go up, baldy’ could be seen as more frivolous, but this would NOT lessen/change the meaning and implications of the ‘scorn’ word in the previous clause.

So, let’s investigate the FIRST action: coming out of the city

It is pretty easy to forget the scale of this, in visualizing what happens on the road, so we need to keep in mind that this is probably an organized mob, which would have required consensus among many of the elite (their supervisors), or at least very strong top-down management pressure:

“That 42 men were mauled by the two bears suggests that a

mass demonstration had been organized against God and Elisha.” [Thomas

L. Constable, “2 Kings,” in The Bible

Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (ed. J. F. Walvoord

and R. B. Zuck; vol. 1; Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1985), 1541–542.]

Since we noted earlier that this mob must be BEHIND Elisha at the turn-around / curse moment, and that they must have operated in stealth (or at least not triggered Elisha’s notice?) before this, the basics of the geography of the path would require them to DELIBERATELY go through the forest for at least the last part of their trip.

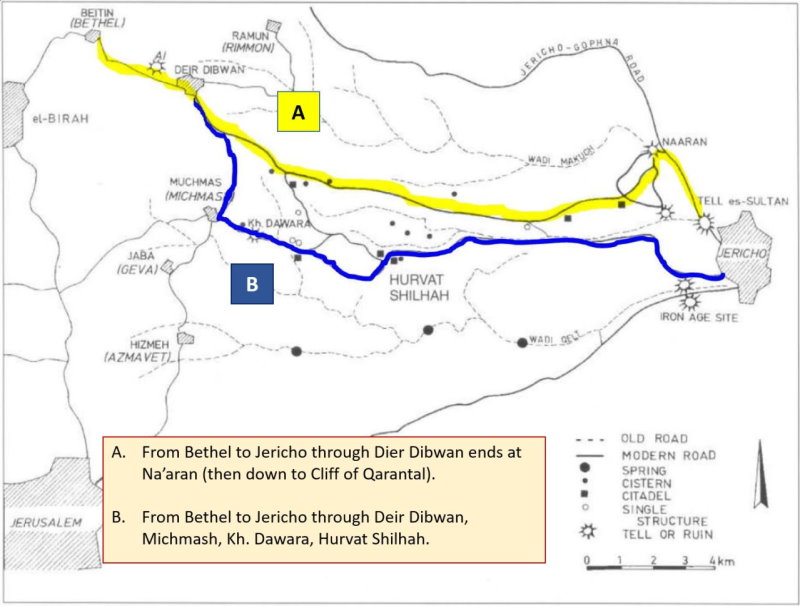

As mentioned earlier, there were two main paths that could have been used for this trip:

[Base map from

Retrieving the Past: essays on

archaeological research and methodology in honor of Gus W. Van Beek ,

Eisenbrauns:1996; “Hurvat Shilhah: An Iron Age Site in the Judean Desert”, A.

Mazar / D. Amit / Z.Ilan. Additional data from David Dorsey, The Roads and Highways of Ancient Israel,

WipfStock: 1991.]

The paths on these routes would not have been as large as the ‘main roads’, and starting from the Jordan plain they would have been reasonably wide, but bounded by cliffs and not forests. About one-third of the way through the trip they would have start up the steppe, coming in the last third into the Central Highlands, where the forests would be thick (mostly with underbrush) and the road very narrow.

Restating the description of roads from earlier:

“From the

Bronze Age up to the Roman period, roads

outside of cities were not paved thoroughfares.

Main roads in the countryside tended to

be 3–4 yards wide (Dorsey, Roads,

19). Depending on the road’s location, it might not be much more than a foot-packed dirt path or

donkey trail on which weeds and thorny scrub would grow (Prov 15:19; 22:5; Hos 2:6).” [ Kevin P. Sullivan

and Paul W. Ferris, “Travel in Biblical Times,” ed. John D. Barry et al., The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham,

WA: Lexham Press, 2016).]

Although designed for ‘two lane traffic’, with a width of 2.75m (3 yards) to 4.5m (4 yards), even the main open roads would have been choked by a group of 50+ people.

“Although

examples of paved streets in Israel have been found, open roads were not paved

before the Roman period. They were constructed by clearing boulders, brush and

other obstacles and then filling in the holes and leveling the surface (Prov

15:19; 22:5; Is 40:3; 57:14; 62:10; Hos 2:6). Maintenance and rebuilding of

roads probably occurred in the spring after the winter rains had ended.

Governments may have been responsible for this task, but local roads probably

were maintained by the local people.

Open roads in ancient Israel were two lanes wide (3–4 m) to allow

traffic to pass in both directions, but wider and narrower roads probably existed.”

[G. L. Linton, “Roads and Highways,” ed. Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M.

Williamson, Dictionary of the Old

Testament: Historical Books (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005),

841.]

At 3 yards wide, each lane is 1.5 yards wide, or 54 inches. At 4 yards wide, each lane is 2 yards wide or 72 inches.

How big is this?

Adult donkeys are about 18 inches wide, and when loaded with side-bags would take up 3 times that width, or 54 inches (one full lane of the smaller road)—or the entire footpath for most forest paths. I doubt that donkeys were used by Elisha on this trip, but I would expect that there would be one or more of the ‘junior prophets’ traveling with him, and perhaps carrying baggage.

The average stride of a modern male in the US is 2.5 feet or 30 inches. If we allow a width of 30 inches (a little cramped, but we are just sizing this somewhat), and add 1 foot of spacing between travelers (so our strides don’t accidently step on others’ sandals/etc), and 6 inches between our shoulders, we get a ‘block’ of space per person of 42 inches in the direction of travel (1.167 yards), and 36 inches in the perpendicular (1.0 yards).

[This is tight—according to published anthropometric data. Published numbers in 2012 for USA males, give a range for ELBOW SPAN (from elbow to elbow when arms are extended fully parallel to ground) as from 31.18 inches (5th percentile) to 36.11 inches (95th percentile).]

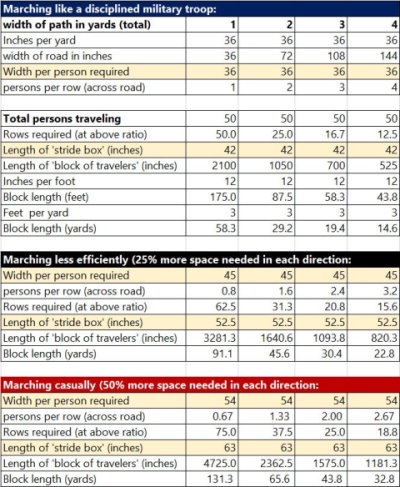

Sizing this at 3 levels of ‘efficiency’ (military, ‘less efficiently” at 25% worse, and “casual” at 50% worse):

We could make a guesstimate as to which of these scenarios might be closest, by sampling some known roads, but with the clear understanding that Roman roads will be different than the original road. They would be paved, and a bit wider, and clearer of debris—especially for those used for military and administrative purposes.

And we should not visualize these roads as somehow ‘straight’ or ‘simple’:

“Geographical Factors in Travel Perhaps the greatest obstacle that travelers and road builders had to overcome was the rugged geographical character of Palestine. The desert regions of the Negev and Judean highlands in the south required the identification of wells and pasturage for the draft animals. The hilly spine of central Palestine forced the traveler to zigzag around steep ascents (such as that between Jericho and Jerusalem) or follow ridges along the hilltops (the Beth-horon route northwest of Jerusalem), or go along watersheds (Bethlehem to Mizpah).” [Victor H. Matthews, “Transportation and Travel,” ed. Chad Brand, Charles Draper, et al., Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary (Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers, 2003), 1615.]

But looking back at the montages given in the first part of this, these numbers look optimistic. But if this visual “estimate” of a MAJOR INTERNATIONAL HIGHWAY (the KINGS HIGHWAY) is true to history, then our tiny mountain passes and narrow wadi-paths will be much, much smaller.

Using the mostly likely path sizes (2 and 3 yards), and the ‘casual’ level of discipline, this block of folks would take up between 44 yards (a little less than half a US football field) and 66 yards (2/3rds of a US football field), and would block the road from other foot traffic.

[If they somehow passed BY Elisha before doing the ‘scorn’ thing [without him seeing them?], then these lengths would double (since they could only use half the road at points).]

It seems obvious to me that these folks had to do part of the trip IN THE WOODS, before emerging behind Elisha to begin their efforts to derail his mission.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

IF that is the case (they DELIBERATELY go into the

woods somewhere and emerge later behind E):

Then they must be more afraid of their superiors—who would have ordered this—than they are of the forest, which is a very, very dangerous position to be in.

Forests were DANGEROUS – and everybody knew it:

“As a

wooded area separate from towns and cultivated fields, the forest is the abode of wild animals, especially nocturnal predators.

We thus find references to “every wild animal of the forest” (Ps 50:10 NRSV),

the “boar from the forest” that ravages a cultivated field without walls (Ps

80:13), “animals of the forest” that “come creeping out” while people sleep at

night (Ps 104:20), “wild animals in the forest” (Is 56:9), “a lion in the

forest” (Jer 12:8; cf. Amos 3:4; Mic 5:8) and a forest in which wild animals devour people (Hos 14:5). Here the

forest is an image of terror.” [Leland Ryken et al., Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity

Press, 2000), 302.]

“Woods and

forests provided a home for animals of various kinds (2 K. 2:24; Ps. 50:10),

and in the pre-exilic period the area known to the Arabs as the Zor, close to

where the Jordan emptied into the Dead Sea, was luxuriant with trees and

tropical vegetation. Asiatic lions

were to be found there also, and it was

deemed an outstanding feat of virility for a man to enter the area and kill a

wild animal unaided (cf. 1 S. 17:35).” [R. K. Harrison, “Forest; Woods,”

ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, The

International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised (Wm. B. Eerdmans,

1979–1988), 338.]

“[H]ow common were predator attacks? Lions and other predators were much more

common in the Middle East than they are today. An attack by a predator was not

considered a rare or surprising occurrence.” [Victor Harold Matthews, Mark W.

Chavalas, and John H. Walton, The IVP

Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (electronic ed.; Downers Grove,

IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), Je 5:6.]

“Lion from the forest (Jer 5:6). Wild animals such as the lion were much

more prevalent in the ancient Near East than they are in modern times. The

metaphor of these wild predators representing the attack of an enemy would have

been readily understood in Jeremiah’s context, particularly among those who

worked as shepherds.” [John H Walton, Zondervan

Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary (Old Testament): Isaiah, Jeremiah,

Lamentations, Ezekiel, Daniel (vol. 4; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009),

248.

“Carnivores. The wild carnivores of Palestine

included the wolf, the lion, the leopard (both spotted and black varieties),

the cheetah, the jackal, and the bear. Recent archaeological excavations have

uncovered remains of both the lion and the bear in Iron Age levels (Martin

1988). While the lion appears to have disappeared before modern times, the bear

survived until early in this century. Tristram (SWP 7), for example, wrote of having seen a Syrian bear (Ursos arctos syriacus) in the Wadi

Hammam. Wolves, leopards, and cheetahs were also still seen as late as the

beginning of this century in Carmel and Galilee. Leopards survive today in

parts of the Judean Desert and the Negeb. … While the lion captured the

imagination of biblical poets (as in Homer, most of the references to the lion

occur in poetic similes), the leopard seems to have had a greater real impact

on human society. Leopard traps from as early as the Chalcolithic period are

found in the ʿUvda Valley in the SE Negeb.” [Edwin Firmage, “Zoology

(Fauna): Animal Profiles,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992),

1143.]

And MORE DANGEROUS THAN ENEMY armies (2 Samuel 18:6-8):

So the army

went out into the field against Israel, and the battle was fought in the forest

of Ephraim. And the men of Israel were defeated there by the servants of David,

and the loss there was great on that day, twenty thousand men. The battle

spread over the face of all the country, and the forest devoured more people that day than the sword.”

Commentators seem to be uncomfortable with such a statement, and offer suggestions on why it really wasn’t the forest itself that devoured the people (the chief suggestion being about the experience of David’s soldiers/warriors):

“The statement that “the fighting was spread over the face of all the country” (עַל פְּנֵי כָל הָאָרֶץ, al peney khal ha'arets, 2 Sam 18:8) means that there was no single massive pitched battle, but rather a series of ambushes and guerrilla attacks, all masked by the heavily wooded terrain. This also is what is meant by the statement in v. 8b about the forest devouring (אָכַל, akhal, “eat”) Absalom’s men.” [Harry A. Hoffner Jr., 1 & 2 Samuel (ed. H. Wayne House and William Barrick; Evangelical Exegetical Commentary; Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2015), 2 Sa 18:7–8.]

“The forest

contributed to David’s victory, for although the Israelite army was defeated by

David’s men (18:7), the forest claimed

more lives that day than the sword (18:8).

The forest did not literally kill men, but Israel’s soldiers were not

accustomed to fighting in a forest, and may have become lost in it as they

fled, so that they died there of thirst and hunger.” [Tokunboh Adeyemo, Africa Bible Commentary (Nairobi, Kenya;

Grand Rapids, MI: WordAlive Publishers; Zondervan, 2006), 401.]

“[t]he forest consumed more troops … than the sword. Clearly the Forest of Ephraim was “not an orderly tree-planted area,

but rough country with trees and scrub and uneven ground, dangerous terrain for

both battle and flight” (Ackroyd). By delaying in Jerusalem on Hushai’s advice,

Abishalom permitted David to cross the Jordan (17:16) and choose for the

battleground the forests of Gilead, which could be compared even to those of

Lebanon for density (Jer 22:6; Zech 10:10), and where the numerically superior

force of Abishalom’s conscript army would be at a disadvantage against David’s

more skilled private army, with its considerable experience of guerrilla

warfare.” [P. Kyle McCarter

Jr, II Samuel: A New Translation with

Introduction, Notes, and Commentary (vol. 9; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven;

London: Yale University Press, 2008), 405.]

“Natural

phenomena are often more deadly than human enemies (cf. Jos 10:11; cf. Conroy,

p. 59 n. 54). Of the many suggestions concerning what it means that the forest

would “devour” more than the sword, McCarter’s seems best: The dense “forest of

Ephraim” (v.6), characterized by uneven and dangerous terrain, was a

battleground “where the numerically superior force of [Absalom’s] conscript

army would be at a disadvantage against David’s more skilled private army, with

its considerable experience of guerrilla warfare” (II Samuel, p. 405).” [Ronald F. Youngblood, “1, 2 Samuel,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary:

Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 & 2 Samuel (ed. Frank E.

Gaebelein; vol. 3; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992), 31019.]

But others include some aspect or assertion about the powerful forces in the forest, even while offering other ‘non-sword’ explanations.

“The

forest claimed more lives that day than the sword (18:8). Whether

through actual casualties (the forest apparently posed various natural dangers;

cf. vv. 9, 17), through temptation to desertion (which would have been

facilitated by the thick cover), or through the advantages that savvy fighters

can exploit in terrain where troop movements are impeded, the forest

contributed to David’s success. Out-numbered but well-trained troops often fare

best in difficult terrain.” [John H. Walton, Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary (Old Testament):

Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 & 2 Samuel (vol. 2; Grand Rapids, MI:

Zondervan, 2009), 468.]

“18:8. forest claimed more lives than the sword. When the Old Testament speaks of land

devouring people (as the forest does here), it is indicating a hostile, inhospitable environment that threatens

survival. Since this was a battlefield chosen by David and not Absalom,

it may be expected that the king’s forces utilized the rough terrain and

forested areas to their advantage. Ambushes, feints drawing troops into ravines

or wadis, and other guerilla tactics may have been employed. Divisions can get

disoriented, lost or isolated and become easy targets.” [Victor Harold

Matthews, Mark W. Chavalas, and John H. Walton, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (electronic ed.;

Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 2 Sa 18:8.

And the classic commentators of the past can state it succinctly:

“The battle

became a rout; scattered over the face of

the country, and the jungle devoured more than the sword] the rocky

thickets were fatal to those who attempted to flee.” [Henry

Preserved Smith, A Critical and

Exegetical Commentary on the Books of Samuel. (International Critical

Commentary; New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1899), 357.]

To me, the explicit contrast is determinative, in identifying the FOREST AS DEVOURER.

· The contrast is between the FOREST-AS-DEVOURER and the SWORD-AS-DEVOURER —not the SWORD-IN-THE-FOREST versus the SWORD-IN-THE-FIELD (i.e. the position of ‘more experienced fighters’ – although that also was true).

· The contrast is between the FOREST-AS-DEVOURER and the SWORD-AS-DEVOURER, and not FOREST-AS-COVER-FOR-DESERTION and SWORD-AS-DEVOURER (i.e. the position of facilitating successful desertions—although that no doubt happened).

· The contrast is between the FOREST-AS-DEVOURER and the SWORD-AS-DEVOURER, and not FOREST-AS-CREATOR-OF-EASY-TARGETS-FOR-THE-SWORD and SWORD-AS-DEVOURER.

And the connection – oddly enough --- can be seen in images of ANIMAL MOUTHS in actual SWORDS of elite soldiers:

“A visual

confirmation of the association of the sword’s “eating” with its blade is

provided by the form of some ANE swords whose hilts connected to the blade in the shape of

the open mouth of an animal.” [Harry A. Hoffner Jr., 1 & 2 Samuel (ed. H. Wayne House and

William Barrick; Evangelical Exegetical Commentary; Bellingham, WA: Lexham

Press, 2015), 2 Sa 18:7–8.]

The forest was so dangerous from its animal population, that when YHWH repeated his eschatological promise of ultimate future protection for those loyal to the covenant in Ezekiel, the fact of danger was often emphasized in the promise:

“I will make with

them a covenant of peace and banish wild beasts from the land, so that they may

dwell securely in the wilderness and sleep in the woods.” [Ezek 34:25]

“No lion shall

be there, nor shall any ravenous

beast come up on it; they shall not be found there, but the redeemed shall

walk there. [Is 35:9.]

“The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the young goat, and the calf and the lion and the fattened calf together; and a little child shall lead them. The cow and the bear shall graze; their young shall lie down together; and the lion shall eat straw like the ox. The nursing child shall play over the hole of the cobra, and the weaned child shall put his hand on the adder’s den. They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain; for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD as the waters cover the sea.: [Isaiah 11]

“Anciently, settlements were endangered by wild animals (Jer 5:6; Prov 22:13); in the blessed

future even their haunts (forests and deserts: Jer 5:6) will be safe,

and even at night (when they

prowl; Ps 104:20f.), because they will be gone.” [Moshe Greenberg, Ezekiel 21–37: A New Translation with

Introduction and Commentary (vol. 22A; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven;

London: Yale University Press, 2008), 702–703.]

One of the

blessings of covenant compliance and loyalty was protection from these fierce animals—even before the

eschatological future:

“And David said, “The LORD who delivered me from the paw of the lion and from the paw of the bear will deliver me from the hand of this Philistine.”

“Because you have made the LORD your dwelling place— the Most High, who is my refuge— no evil shall be allowed to befall you, no plague come near your tent. For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone. You will tread on the lion and the adder; the young lion and the serpent you will trample underfoot. [Psalm 91:9ff]

I will eliminate (vicious

beasts from the land). wĕhišbattî,

literally “cause to cease.” According to the rabbis (Sipra Beḥuqotay 2:1), this can be done in two ways: by

removing them (R. Judah; cf. Ezek 34:25) or neutralizing them (R. Simeon)—that

is, by changing their nature (Isa 11:9a; Ramban; Job 5:23; Hoffmann 1953).

Philo (Praem. 88) connects the two

halves of verse: “that when the wild beasts within us are fully tamed, the

animals too will become tame and gentle.” …In biblical times, lions and bears

inhabited Canaan (Judg 14:5; 2 Kgs 2:24; Isa 11:6–7; cf. Gen 9:5; 37:33; 1 Kgs

13:24–25; Sefire I A: 30–32). Lions reappeared after the destruction of North

Israel and preyed on the new settlers (2 Kgs 17:24–28; cf. Exod 23:29). One can

thus comprehend the implication of this blessing that man alone is incapable of

coping with this menace: its resolution can stem only from YHWH (see also Hos

2:20; Job 5:23).” [Jacob Milgrom, Leviticus

23–27: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (vol. 3B; Anchor

Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 2296.]

“The

blessing of safety from wild animals is promised in Lev. 26:6; Hos. 2:20; cf.

Isa. 11:6–8; cf. Job 5:22–23.” [Jeffrey H. Tigay, Deuteronomy

(The JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996),

309.]

And one of the

last-resort penalties for covenant non-compliance was WITHDRAWAL of

protection from predators and even bereavement of children due to wild

animal activity. And this animal action was linked to TRAVEL ON THE ROADS:

“Then if

you walk contrary to me and will not listen to me, I will continue striking

you, sevenfold for your sins. 22 And

I will let loose the wild beasts against you, which shall bereave you of your children and destroy your livestock and make you few in number,

so that your

roads shall be deserted.” [Le 26:21–22]

“I will send famine and wild beasts against you, and they will rob you

of your children” [Eze 5:17]

“If I cause

wild beasts to pass through the land, and they ravage it, and it be made

desolate, so that no one may pass

through because of the beasts, even if these three men were in it, as I

live, declares the Lord God, they

would deliver neither sons nor daughters. They alone would be delivered, but

the land would be desolate” [Ezek 14:15-16]

And if you remain

hostile toward Me, I will loose wild beasts against you The Hifil form used here, ve-hishlaḥti, is rare in biblical

Hebrew. It conveys the sense of “driving” the beasts through the land.

This threat is the reverse of the Blessing stated in verse 6. --- and they shall bereave you of your

children The verb sh-kh-l is

used specifically to connote the loss of children or with respect to animals,

the loss of young. --- They shall

decimate you Deserted roads are

often depicted as a feature of wars and invasion in biblical literature.

Compare Lamentations 1:4: “Zion’s roads are in mourning.” Similar themes occur

in Isaiah 33:8; Ezekiel 30:3–4; and in Psalms 107:38.” [Baruch A. Levine, Leviticus (The JPS Torah Commentary;

Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 186–187.

“Fanged beasts … venomous creepers in dust Wild animals, such as lions or bears,

and poisonous snakes. Settled territory was often in danger of being overrun by

wild animals; the threat of that is one of the curses in Leviticus 26:22.”

[Jeffrey H. Tigay, Deuteronomy (The

JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996), 309.]

“I will let loose wild beasts

against you. Reversing “I will eliminate vicious beasts from the

land” (v. 6bα; Bekhor

Shor). The Hipʿil wĕhišlaḥtî

bĕkā with the beth of

hostility is attested elsewhere, such as hinĕnî

mašlîaḥ bĕkā ‘behold, I am sending against you’ (Exod 8:17;

cf. 2 Kgs 15:37; Ezek 14:13; Amos 8:11 [also punishments]). The outbreak of

wild beasts is frequently regarded as a punishment for sin (Deut 32:24; 2 Kgs

2:24; 17:25; Isa 13:21, 22; Ezek 5:17; 14:15; cf. Hillers 1964: 54–56).

Weinfeld (1993: 191, n. 17) aptly points to a similar series of punishments of

drought, wasteland, and wild animals (vv. 20–22) that appears in the Sefire

treaty 1A 27–28 (eighth century B.C.e).

--- “they shall bereave you.

Reversing “and (I) shall make you fruitful” (v. 9aβ); note the emphasis on pĕrî ‘fruit, offspring’. Ezekiel

repeats this verse almost verbatim (Ezek 5:17; cf. 14:15). --- “make you few. wĕhim ʿîṭâ ʾetkem

(cf. Ezek 29:15b). This statement is not redundant in view of the previous

“they shall bereave you,” since its purpose is to reverse the blessing wĕhirbêtî ʾetekem ‘multiply

you’ (v. 9aγ; Ḥazzequni).

Perhaps, this explains why hirbêtî is

separated from hiprêtî in v. 9 in

order to be matched by two distinct curses.

“and your roads

shall be deserted. The same

sequence, wild beasts and deserted roads, is found in Ezekiel: “Or, if I were

to send wild beasts to roam the land and they depopulated it, and it became a desolation with none passing

through it because of the beasts” (Ezek 14:15; cf. Judg 5:6; Isa 33:8; Lam

1:4). This is a standard curse in the

ancient Near East: “That no one tread the highways, that no one seek out

the roads” (ANET 612, 1. 39).” [Jacob

Milgrom, Leviticus 23–27: A New

Translation with Introduction and Commentary (vol. 3B; Anchor Yale Bible;

New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 2296.]

“Ezek 5:17. famine and wild beasts. These two punishments are related only

as part of a typical group of punishments that deity is inclined to send (two

more, plague and bloodshed, occur in the second half of the verse). As early as

the Gilgamesh Epic in Mesopotamia, the god Ea had reprimanded Enlil for not

sending lions to ravage the people rather than using something as dramatic as a

flood. The gods used wild beasts along with disease, drought and famine to

reduce the human population. A common threat connected to negative omens in the

Assyrian period was that lions and wolves would rage through the land. In like

manner, devastation by wild animals was one of the curses invoked for treaty

violation (see also Deut 32:24).” [Victor Harold Matthews, Mark W. Chavalas,

and John H. Walton, The IVP Bible

Background Commentary: Old Testament (electronic ed.; Downers Grove, IL:

InterVarsity Press, 2000), Eze 5:17.]

“2:12. punishment by wild animals. The eighth-century Aramaic inscription

from Deir’Alla that contains the prophecy of Balaam and the twentieth-century

Egyptian Visions of Neferti both

describe an abandoned land in which strange and ravenous animals forage for

food. Ravaging wild beasts were considered one of the typical scourges that

deity would send as punishment.´ [ Victor Harold Matthews, Mark W. Chavalas,

and John H. Walton, The IVP Bible

Background Commentary: Old Testament (electronic ed.; Downers Grove, IL:

InterVarsity Press, 2000), Ho 2:12.]

And these types of dangers and issues were prevalent in the ANE nations around them – also enshrined in such treaties:

“Thereby

Yahweh stresses the severity—i.e., violence—of the coming destruction. In vv 7

and 8a, the lion (שחל), leopard (נמר) and bear (דב) typify devouring animals (cf. 1 Sam 17:34–37). The attack of wild animals was a common

curse motif in ancient Near Eastern covenant

sections (Hillers, Treaty Curses and the Old Testament Prophets,

54–56). Lev 26:22 (“I will send wild animals against you …”) and Deut 32:24

(“The teeth of animals I will send upon them; with the venom of creatures that

crawl in the dust …”) present this motif in the Sinai covenant (cf. Lam

3:10–11; Isa 5:29–30; 7:18; 14:29; 15:9; 56:9; Jer 2:14–15; 4:7; 12:9; 48:40;

49:22; 50:44; Hos 5:14; Hab 1:8). In these references the lion is described

most often, though a variety of animals

from bees to wolves are also mentioned as animal agents symbolic of divine

wrath. --- The attack of the “animals” will kill, not merely maim. .” [Douglas

Stuart, Hosea–Jonah (vol. 31; Word

Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1987), 204.

“Among the common

varieties of curse found in ancient Near Eastern treaties

and related biblical literature are threats of being attacked and killed by ravenous animals and of having one’s corpse desecrated by being

eaten by such animals. --- The eighth-century

Aramaic treaties from Sefire in northern Syria

contain the following curse against a would-be rebel: ‘May the gods send every

sort of devourer against Arpad and against its people! [May the mo]uth of a

snake [eat], the mouth of a scorpion, the mouth of a bear,

the mouth of an ant …’ (Sefire

1.A.30–31). --- Another of the Sefire curse lists threatens with: ‘the mouth of

a lion, the mouth of a [wol]f,

the mouth of a panther’ (Sefire 2.B.9). The Akkadian treaty of Esarhaddon with

Baal of Tyre says similarly, ‘May Bethel and Anath-Bethel deliver you to a man-eating

lion’ (rev. IV 6–7; Reiner 1969: 534). --- And Ashurbanipal’s annals relate

that he punished the fugitive Arab king Uaiṯe’ I by locking him up in a

cage with a dog and a bear (Eph‘al

1984: 143–44 and n. 501).” James M. Lindenberger, “What Ever Happened to

Vidranga? A Jewish Liturgy of Cursing from Elephantine,” in The World of the Aramaeans III: Studies in

Language and Literature in Honour of Paul-Eugène Dion (ed. P. M. Michèle

Daviau, John W. Wevers, and Michael Weigl; vol. 326; Journal for the Study of

the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press,

2001), 326149.]

And the danger from animals in the FOREST was compounded (as noted also above) with danger from animals ON THE ROADS:

“Two Egyptian

literary documents from the late 13th century B.C. warned of the problem of wild beasts. “A soldier,

when he goes up to Retenu (i.e., Palestine),” says the one text, “has neither

staff nor sandals. He does not know whether he is dead or alive, by reason of

fierce lions” (Waterhouse 1963: 160). Of conditions along a Canaanite roadway,

the other papyrus utters, “Lions are

more numerous than leopards or bears, (and the road is) surrounded by

Bedouin on (every) side of it” (ANET,

477). Wild beasts were also a formidable threat to travel, as described

in the Bible. Samson is said to have encountered a young lion on the Sorek

valley road between Zorah and Timnah (Judg 14:5–6). Citing evidence that he was

a worthy opponent of the giant Goliath, David boasted that he had slain bears

and lions while tending his father’s sheep along Judean pathways (1 Sam

17:34–36). … Travelers

on roads that aligned the Jordan river valley must have faced the same reality: the Medeba map depicts a lion on the prowl in the valley (cf. Jer

50:44; Mark 1:13); many Arabic towns in this valley appear to bear the names of

beasts; skeletal remains of beasts have been exhumed from the Jordan’s flood

plain; and mention is frequently made in itineraries of the sighting of beasts

in this valley.” [Barry J. Beitzel, “Travel and Communication: The Old

Testament World,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The

Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 646.]

“Travelers

faced the danger of predators, such

as lions (e.g., Judg 14; 1 Sam

17:34–37; Amos 5:19) and bears

(e.g., 2 Kgs 2:23–24; Amos 5:19; Prov 28:15). The Bible also mentions wolves,

jackals, and hyenas.” [Kevin P. Sullivan and Paul W. Ferris, “Travel in

Biblical Times,” ed. John D. Barry et al., The

Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

So, this first

action puts this mob into imminent danger from wild beasts of the

forest—whether their intentions were good or not. The expectation of the

culture was that they would be in danger BOTH in the forest AND on the road

(i.e. the references to predators attacking people on the roads).

…………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………….

SECOND ACTION: “SCORN”

So, let’s investigate the scorn word (QeLeS) for its import on the events.

First of all, our word is very

rare in the Hebrew Bible, and not really used for ‘normal level’ mocking and

taunting.

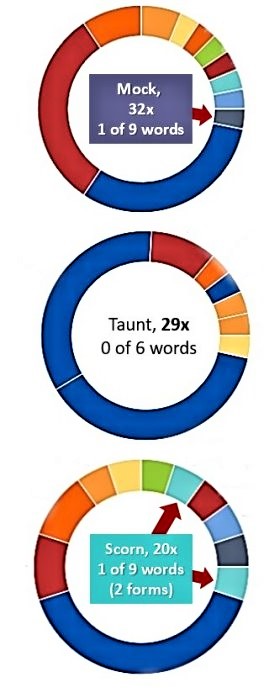

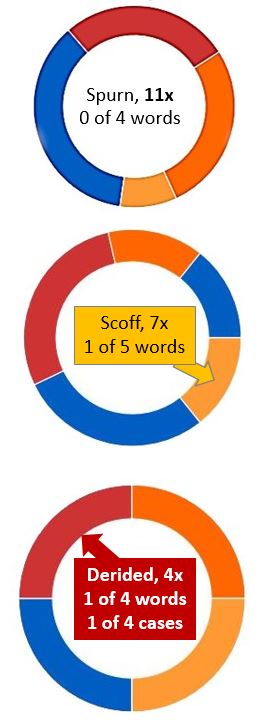

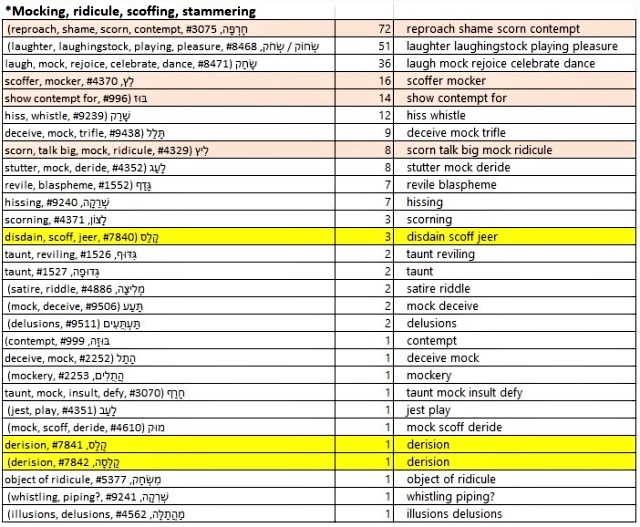

If we pull up all the words/phrases that are translated [ESV] as mock, taunt, scorn, spurn, scoff, derided, and jeered, this becomes very obvious. We have a little over 100 occurrences of such words, with the various forms of those words generating at least 267 total occurrences.

Here are visual representations of those words (in descending frequency), with the number of Hebrew words used, and if our QLS (“scorn”) word is ever translated by that English word.

How to read the bubbles:

· The outer ring represents 100% of all the times that some version of the English word in the center occurs.

· Each colored segment in this ring represents the relative number of times a Hebrew word (or form) is translated by that English term. In other words, if one-fourth of the ring was GREEN, then 25% of all occurrences of the English term came from the SAME HEBREW word.

· In the center of the ring, is the English term, the number of times it shows up (which equals 100% of the outer ring, obviously), the number of Hebrew words/forms that are translated by that English term, and an indication of whether our QLS scorn word is used.

· If it is NOT used to generate that particular English word, the center simply has “0 of X words”.

· If it IS used to generate that particular English word, the center points to the segment(s) on the other ring generated by our word – to gauge how often it is used to represent that notion. A small segment means it is uncommon for that English word; a larger segment indicate more common.

Here is that data in tabular form:

|

English Gloss |

Core Case count |

Number of Hebrew words |

QLS? |

Is QLS > 50% of cases (outer ring)? |

|

Mock |

32 |

9 |

1 |

No |

|

Taunt |

29 |

6 |

0 |

No |

|

Scorn |

20 |

9 |

1 |

No |

|

Spurn |

11 |

4 |

0 |

No |

|

Scoff |

7 |

5 |

1 |

No |

|

Derided |

4 |

4 |

1 |

No |

|

Jeer |

3 |

2 |

1 |

No |

You can see that in these core cases, it is very infrequently used for these more ‘normal level’ mocking, scoffing, and jeering.

We can also see this from the frequency of Hebrew words sometimes translated into mocking-type words. This table (accurate but NOT comprehensive) includes 267 of the various English translations of essentially ALL of the Hebrew word, forms and/or phrases used for this purpose (omitting ‘despise’ as a ‘scorn’ word). The leftmost and right most columns contain the basic lexical data of definitions and nuances, with the leftmost containing the Hebrew form (not lemma, which we just looked at). The center column has the number of times that Hebrew construction is used for the English concepts on the right.

Our word is highlighted in yellow, and the main words that would be used for taunts about someone’s personal appearance (lol) are highlighted in pale red. It doesn’t even make the top 10.

Our QLS root is used in only 8 places in the Hebrew bible:

· 4 verbal forms: 3 in our verbal Hithpael stem and 1 in a the Piel stem (translated ‘despise’ with a core of ‘scorn’)

· 3 masculine noun forms - Ps 44:13, Ps 79.4, Jer 20.8 (scorn, derided, derision)

· 1 feminine noun form - Ezek 22.4 (mockery)

When we add the 3 cases NOT represented in the table above, we get a table total of 270, and a QLS-related total of 8 – that is slightly less than 3%. This word is RARE, and only ‘brought out for special occasions’ (smile).

When we approach it from the Hebrew verb side, we can understand why it is not represented in these ‘normal’ mock words: it is a super-strong word…

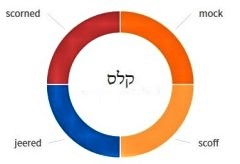

When we put our Hebrew verb in the center of the circle, we get 4 English words commonly used to translate it.

Of the 3 other cases of our word, only 2 match our verb stem form (hithpael) here: Habakkuk 1:10 and Ezekiel 22.5.

[Briefly, the third case in Ezekiel 16:31: (a) uses a Piel stem, (b) does not refer to persons, (c) is not accompanied by a speech act, and (d) is in a highly figurative passage, but it still reflects the word’s vehemence and arrogant rejection of its object, by an agent who considers herself above the law:

“How sick is your heart [Jerusalem] declares the Lord GOD, because you did all these things, the deeds of a brazen [sallatet, Lit. “ruling”; i.e., who does what she pleases, being subject to no one (Kara). J. C. Greenfield (Eretz-Israel 16 [1982], 56–61; English summary, 253*); “headstrong, domineering”, NIDOTTE.] prostitute, building your vaulted chamber at the head of every street, and making your lofty place in every square. Yet you were not like a prostitute, because you scorned [qilles] payment. … Men give gifts to all prostitutes, but you gave your gifts to all your lovers, bribing them to come to you from every side with your whorings.”

“These

verses expand on Jerusalem’s high-handed behavior. First, she has broken

the generally accepted norms of a

prostitute’s behavior by scorning payment. … Jerusalem has reversed the

customary roles of payer and payee in harlotrous relationships. Whereas

prostitutes generally follow their profession as a means of livelihood, Jerusalem has

scorned the payment that men normally pay for a woman’s sexual favors. Worse

yet, she has bribed them to satisfy her lusts, stifling all sense of shame, and

inverting normal roles of prostitute and client. The resources that

Yahweh had bestowed liberally on her she dispensed to her lovers (mĕʾahăbayik, v. 33), all

the surrounding nations.” [Daniel Isaac Block, The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 1–24 (The New International

Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

Co., 1997), 497–498.]

The motif of replacement of something ‘reasonable’ (receiving payment for services) for something ‘unreasonable’ (making payment for services) reflects a complete reversal of values, and is stated in terms of our word – ‘scorning’—to the point of REJECTION and REPLACEMENT.]

……………………………………………………………………………………….

The two OTHER cases of this verb

reveal how INTENSE and SHOCKING this word actually is.

The first one is from Habakkuk and the other from another passage in Ezekiel.

ONE: The passage from Habakkuk (1:10) is the clearest one for getting to the core of this usage by the [N]. Speaking of the Babylonian armies, the text reads:

“At kings they scoff (qls, our word), and at rulers they laugh (mshkq).”

Commentators draw attention to the abject arrogance and anti-authority position of this army:

§ “The corollary of Babylonian autonomy is contempt for all other authority, which

is evaluated in purely military terms. The Babylonians “deride kings” and

“scoff at rulers,” since they can “laugh” at their defenses.” [Carl E.

Armerding, “Habakkuk,” in The Expositor’s

Bible Commentary: Daniel–Malachi (Revised Edition) (ed. Tremper Longman III

and David E. Garland; vol. 8; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008), 8615.]

§ “The contempt of the Chaldeans for foreign

rulers, whom they can subdue with the greatest of ease, is exactly like

that of their predecessors, the Assyrians (2 Kgs 18:33–35, where they ridicule

the gods).” [Francis I. Andersen, Habakkuk:

A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (vol. 25; Anchor Yale

Bible; New Haven; London: Yale

University Press, 2008), 157.]

§ “They were fierce, cruel people who never

tired in pursuit of their goal of conquest. Their successes struck fear into

the hearts of all who stood in their path. A terror and dread to all, they arrogantly

acknowledged no law but themselves. … No wonder, then, that enemy rulers were merely

a joke to them. With disdain they laughed at them and moved against

their cities, however strongly fortified. …

Its armies have been portrayed as the finest and fiercest in the world,

being capable of moving swiftly across vast stretches of land to strike the

enemy. Babylon

was an arrogant bully who contemptuously mocked all its foes and knew no god

but strength.” [Richard D. Patterson and Andrew E. Hill, Cornerstone Biblical Commentary, Vol 10:

Minor Prophets, Hosea–Malachi (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers,

2008), 408.]

§ “So he at kings will mock; and sovereigns are a joke to him. Israel always previously had been able

to count on buffer nations to absorb the lethal blows of invaders. But this adversary makes fun of the most

powerful figures of the earth. How then may the remnant of Judah expect to

resist successfully the invasion of this enemy? [O. Palmer Robertson, The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah

(The New International Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm.

B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1990), 154–155.]

§ “Everyone

should fear one in whom no fear exists. The Babylonian army mocked kings and made rulers objects of derision. They

had “contempt

for all other authority.” … Though no one else would dare do so, they

scoffed and made sport of the rulers of the people. If the army did not tremble before kings, what

could the common people do? Nothing could stand before the Chaldean army. The

Babylonians (again emphasized) laughed at the fortresses of the nations.”

[Kenneth L. Barker, Micah, Nahum,

Habakkuk, Zephaniah (vol. 20; The New American Commentary; Nashville:

Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1999), 307–308.]

§ “Confident in their strength, the

Babylonians scoffed at kings and

ridiculed rulers. It was their custom

to exhibit captive rulers as public spectacles. Their brutality is seen in

the way they treated Zedekiah after Jerusalem fell. They killed his sons before

his eyes and then, with that awesome sight burned into his memory, they put out

his eyes, bound him in shackles, and took him prisoner to Babylon (2 Kings

25:7). … But not only did the Babylonians scoff at their foes; they also laughed at all fortified cities (lit., “every fortress”). They poured

derision on the strongholds which their victims considered impregnable.” [J.

Ronald Blue, “Habakkuk,” in The Bible

Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (ed. J. F. Walvoord

and R. B. Zuck; vol. 1; Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1985), 11510.]

TWO: The passage from Ezekiel 22.4-5 reveals the same level of arrogant de-valuation (deserved in this case) and trivialization:

“Therefore I have made you a reproach [herpa] to the nations, and a mockery [qallasa, a noun form of our

word] to all the countries. Those who are near and those who are far from you

will mock [our word, QLS] you…”

Commentators note how ‘low’ a status this is, and how the hostility of the nations is connected to Jerusalem’s hostility to the Law:

“Both moral

and cultic sins were reviewed to show the hostility that existed for the law.

… The first two sins mentioned included bloodshed and idolatry. … Disregard for

the law of God led to a dramatic increase in crimes of violence so that

Jerusalem was called the “city of bloodshed”. [Lamar Eugene Cooper, Ezekiel (vol. 17; The New American

Commentary; Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1994), 217.]

“The acts of

idolatry and bloodshed bring God’s judgment near. Jerusalem has come of age for

judgment. She will become a reproach to the surrounding nations, both far and

near. They will laugh at her miserable state

and her

infamous reputation (vv. 4b–5).” [Ralph H. Alexander, “Ezekiel,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary:

Jeremiah–Ezekiel (Revised Edition) (ed. Tremper Longman III and David E.

Garland; vol. 7; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2010), 7761.

But Block picks up on an intersecting theme from Deuteronomy:

“The

accusation concludes with an elaboration of the nations’ response to

Jerusalem’s fate. Those near (ḥaqqĕrōbôt)

and far away (hārĕḥōqôt)

represent a merismic word pair for “all nations” who mock (yitqallĕsû) her for her “defiled reputation” (ṭĕmēʾat haššēm)

and the “magnitude of her tumult” (rabbat

hammĕhûmâ). Although

Ezekiel employs vocabulary different from Deuteronomy, the present

statement reflects intense disappointment over Jerusalem’s failure to achieve the

Deuteronomic vision for the nation: to be exalted over the nations for praise (tĕhillâ),

fame (šēm), and honor (tipʾeret) (Deut. 26:19; cf. Jer.

13:11; 33:9). Now she must prepare for the full force of the covenant curse: becoming the

object of astonishment/horror (šammâ),

a proverb (māšāl), and a

byword (šĕnînâ). Yahweh cannot

stand idly by while life is cheapened and his claim to exclusive allegiance is

trampled underfoot. When he is through with the city the din of rebellion

within her walls will have been exchanged for the external taunts of the nations.” [Daniel Isaac Block, The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 1–24 (The

New International Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B.

Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1997), 705–706.]

In the

Deuteronomy passages, being SCORNED and DETESTED (e.g., a ‘horror’) was one of

the major penalties of covenant non-compliance.

After

listing the blessings / benefits of covenant compliance (Deut 28:1-14), the

penalties are listed: destruction, disease, drought, defeat in battle, physical

and mental diseases of Egypt, oppression and theft, exile and revulsion by the

nations (28.36-37), and crop failure and economic ruin.

Verse 37 reads like this:

And you shall become a horror, a proverb, and a byword among all the peoples where the LORD will lead you away.

And it is echoed/explained often throughout the prophets, as they try to steer the king and the people back onto compliance (and its blessings):

“… then I will cut off Israel from the land that I have given them, and the house that I have consecrated for my name I will cast out of my sight, and Israel will become a proverb and a byword among all peoples” [1 Ki 9:7]

“I will make them a horror to all the kingdoms of the earth, to be a reproach, a byword, a taunt, and a curse in all the places where I shall drive them.” [Je 24:9–10.]

What this means for us, is that the use of this same word to describe the action of the people in our passage, links it with two things:

(1) Complete rejection of authority; and

(2) Complete devaluation of the authority (as if Elisha were being rejected and/or punished by YWHW as being evil , like Jerusalem in Ezekiel).

……………………………………………

Summary of the ‘scorn’ word/action: The word is a VERY strong word, actually. It is NOT the normal word for ‘taunt’ (chrp) nor basic mocking (various words). This word is about SCOFFING / REJECTION / DEVALUATION of legitimate authority, based upon one’s OWN assertion of self-authority:

“Each

occurrence of this root describes actions that either contradict customary practices (e.g., Ezek 16:31) or flaunt acceptable standards (e.g., 2

Kgs 2:23; Jer 20:8; Hab 1:10). The

attitude of disdain and its accompanying behavior are consistently directed toward authority

figures, especially when individuals are the perpetrators (e.g., 2 Kgs

2:23; Jer 20:8). “ [Willem VanGemeren, ed., New

International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology & Exegesis (Grand

Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1997), 929.]

Strictly speaking, we could stop right here – with

full justification for the action of YHWH in inflicting a pre-announced,

statutory treaty penalty.

Not only is this COMPLETELY contrary to ethical standards of how messengers/prophets were supposed to be treated, it is also the highest LEVEL of repudiation, insult, rejection, and REVOLT against the suzerain YHWH and his emissary.

It is – at the same time – a clear statement of what will be the Northern kingdom’s demise, and that of Judah’s as well:

“The LORD, the God of their fathers, sent persistently to them by his messengers, because he had compassion on his people and on his dwelling place. But they kept mocking the messengers of God, despising his words and scoffing at his prophets, until the wrath of the LORD rose against his people, until there was no remedy.” [2 Chronicles 36.16]

These were not foreigners repudiating YHWH, but the citizens of a vassal kingdom (Israel was still bound to YHWH under the treaty, regardless of any changes in government structure). What does a king do when his/her subjects refuse to follow the rules of the authorities, even to the point of VOCAL DENOUNCIATIONS?

Let’s ask Jesus (smile):

· Parable of the 10 Minas (Luke 19): “He said therefore, “A nobleman went into a far country to receive for himself a kingdom and then return. Calling ten of his servants, he gave them ten minas, and said to them, ‘Engage in business until I come.’ But his citizens hated him and sent a delegation after him, saying, ‘We do not want this man to reign over us.’ When he returned, having received the kingdom, he ordered these servants to whom he had given the money to be called to him, that he might know what they had gained by doing business. [SNIP] But as for these enemies of mine, who did not want me to reign over them, bring them here and slaughter them before me.’”

· The Parable of the Wedding Feast (Matthew 22): “And again Jesus spoke to them in parables, saying, “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who gave a wedding feast for his son, and sent his servants to call those who were invited to the wedding feast, but they would not come. Again he sent other servants … But they paid no attention and went off, … while the rest seized his servants, treated them shamefully, and killed them. The king was angry, and he sent his troops and destroyed those murderers and burned their city. Then he said to his servants, ‘The wedding feast is ready, but those invited were not worthy. Go therefore to the main roads and invite to the wedding feast as many as you find.’ … So the wedding hall was filled with guests.

…………………

THIRD ACTION: Chanting “go up, baldy”

Their third action – ‘saying’

something – is fairly obscure to us, but not something that needs to be clearly

understood. The ‘scorn’ word up above is enough for

triggering YHWH’s action, but this clause adds an extra element of oddness to

this.

Their

statement has two parts: ‘go up’ and “baldhead”.

The Go UP verb

has already been used twice in the passage already: “Elisha went up to Bethel” and “As He was going up”.

Since our

passage is said to happen while he was in transit, one would easily

think that this group was somehow using the word in the same sense – “go

ahead, go on up – you!”. Even with the possible element of ‘baldness’, it is

not obvious to me why this might count as a taunt in itself (and certainly less

so, without the ‘baldness’ word)?

Commentators—wrestling

with this --- surface some of the obvious choices, all of which have SOMETHING

to commend them:

“Go away, baldy! Lit., “go on up, baldy” (‘aleh

qereakh [TH7142, ZH7944]). The root ‘alah [TH5927, ZH6590]

regularly conveys the idea of “going up” or “ascending,” and that is the idea

here (the same root is already used twice in the verse, indicating Elisha’s

“going up” to Bethel and “walking along” the road [uphill?]). A number of

commentators, however, prefer the basic idea of “going away” or “departing” for

the present text (cf. NRSV; also Cogan and Tadmor 1988:38), so the NLT

translation here is quite defensible. Still,

those who read here a sardonic challenge for the bald Elisha to “go on up” as

the very hairy Elijah (cf. 1:8) recently did, have a point.” [William H. Barnes, 1-2 Kings (ed. Philip W. Comfort; vol. 4b; Cornerstone Biblical

Commentary; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2012), 206.]

“The

jeering “Go on up!” may be a reference to Elijah’s translation, with the sense

of “Go away like Elijah,” perhaps spoken in “contemptuous disbelief.” [[1] Paul R. House, 1, 2 Kings (vol. 8; The New American

Commentary; Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1995), 260–261.]

“As Elisha was traveling

from Jericho to Bethel several dozen

youths (young men, not children)

confronted him. Perhaps they were young false prophets of Baal. Their jeering,

recorded in the slang of their day, implied that if Elisha were a great prophet

of the Lord, as Elijah was, he should go

on up into heaven as Elijah

reportedly had done.” [Thomas L. Constable, “2 Kings,” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures

(ed. J. F. Walvoord and R. B. Zuck; vol. 1; Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1985),

1541–542.]

The spatial

arrangement is important here.

·

After

they say this, Elisha turns around and ‘sees them’, and then does his

judgment thing.

·

He is headed UP to Bethel at this point.

·

They came out of the city [presumably Bethel], but are now behind

him (either passing him first, or going through the woods first and then

emerging behind him)—or some mix of the two.

·

Their one-word imperative ‘go up’ makes perfect geographical sense.

We can more or less eliminate the meaning ‘go away’, since the normal words for that would be hlk (e.g. “depart and go to the land of Judah”)—like is used when he leaves Bethel for Mount Carmel-- or swr (“Go, depart; e.g., go down from among the Amalekites).

Okay, let’s see if the

‘baldness’ thing can help with this—

They use the adjective qereach for this, which only occurs two other times … sigh.

But the root of this word is about shaving one’s head, so it might not be about some kind of natural baldness to begin with. But it’s quite murky—from TWOT:

2069a קֵרֵַח

(qērēaḥ) bald.

2069b קָרְחָה (qorḥâ) baldness.

2069c קָרַחַת (qāraḥat) back

baldness.

Our root denotes the lack of hair on the

human head. This may result from shaving

(Mic 1:16, where gāzaz “to

shear” is the parallel; Job 1:20; Jer 7:29), from plucking (māraṭ,

Neh 13:25), from leprosy (Lev

13:42), and other and natural causes

(Lev 13:40?). For synonyms see gāzaz,

and gibbēaḥ (forehead

baldness). The root occurs twenty-three times.

Ritualistic shaving of the head in imitation of Canaanite

mourning rites is prohibited for priests

(Lev 22:24; cf. Jer 41:5) and laity

(Deut 14:1), because as holy servants and children of God they were to keep

themselves as from all idolatry (cf. Barnes on Mic 1:16). Not all baldness,

however, is unclean (Lev 13:40). Indeed, not all shaving of the head to express mourning

is prohibited. God commands (Mic 1:16) and expects his people (Isa

22:12) to show deepest mourning over their sin. His punishment will effectuate

mourning over their dead (Ezk 7:18; Isa 3:24), but even such tragedy will not

humble them. Ultimate judgment is preceded by a picture of widespread death and

a prohibition of mourning (Jer 16:6). Baldness is a picture of mourning (Jer 47:5).

… The taunt (J. W. Kapp, “Baldness” ISBE, I, p. 380f.) hurled at Elisha (II Kgs

2:23) is especially ignominious because it showed abject disrespect for God’s

prophet (qālaṣ, q.v.) and

God himself. According to the Law, death was the punishment (cf. qālal and

Lev 20:9). [Leonard J.

Coppes, “2069 קָרַח,” ed. R. Laird Harris,

Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological

Wordbook of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1999), 815.]

This would not

be the baldness of the forehead, since that had its own word:

גִּבֵּחַ (gibbēaḥ), adj. bald

in the forehead (#1477); גַּבַּחַת (gabbaḥat),

nom. bald forehead” [NIDOTTE]

Some take our

word as baldness on the BACK of the head (which would only be visible from BEHIND

Elisha…):

“(qē·rēaḥ):

adj.; ≡ Str 7142; TWOT 2069a—LN 8.9–8.69 bald, bald-headed, i.e., pertaining to having no hair on the back part

of the crown of the head as is common in male-pattern baldness (Lev 13:40;

2Ki 2:23(2×)+)” [James Swanson, Dictionary

of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains : Hebrew (Old Testament) (Oak

Harbor: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997).

We have

already noted the possibility that his head would not have been visible

due to headwear, but assuming for the moment that the head was

uncovered, let’s see what our options are for understanding this:

“go up, baldy.” The paucity

of references to the physical characteristics of prophets in the OT throws this

into sharp relief. It is in direct contrast to the identifying features of

Elijah (1:8). Since artificial baldness was legislated against in Israel

(Deut 14:1), Elisha’s condition was a

natural one.” [T. R. Hobbs, 2 Kings

(vol. 13; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1985), 24.]

“If Elijah was a

hairy man, Elisha’s baldness would be a stark

contrast and perhaps suggest to some that he could never have the same

powers as his master. This taunt would therefore be a disavowal of his

prophetic office and calling and would be strikingly refuted by the immediate

fulfillment of his curse. Therefore in verses 19–22 Elisha removed a curse,

while in 23–24 he effectuated a curse.” [Victor Harold Matthews, Mark W.

Chavalas, and John H. Walton, The IVP

Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (electronic ed.; Downers Grove,

IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 2 Ki 2:23.]

“The reference to the baldhead

is not clear, but Elisha might have already been so bald by nature that to

youthful eyes he looked grotesque; or perhaps some prophets, like later Christian

monks, shaved their heads as a mark of their vocation” [Crossway Bibles, The ESV Study Bible (Wheaton, IL:

Crossway Bibles, 2008), 649.]

“Baldness, regarded as a disgrace, was

here an epithet of scorn (cf. Isa 3:17, 24).” [R. D. Patterson and Hermann J.

Austel, “1, 2 Kings,” in The Expositor’s

Bible Commentary: 1 & 2 Kings, 1 & 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah,

Esther, Job (ed. Frank E. Gaebelein; vol. 4; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

Publishing House, 1988), 4178.

“The epithet baldhead may allude to lepers who had to shave their heads and were

considered detestable outcasts. Or

it may simply have been a form of scorn, for baldness was undesirable (cf. Isa.

3:17, 24). Since it was customary for men to cover their heads, the young men

probably could not tell if Elisha was bald or not.” [Thomas L. Constable, “2

Kings,” in The Bible Knowledge

Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures (ed. J. F. Walvoord and R. B.

Zuck; vol. 1; Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1985), 1541–542.]

“Other

traditions, however, especially in the prophetic tradition suggest that shaving

heads or beards as a sign of mourning or judgment was practiced (Amos 8:10;

Isa 22:12; Jer 41:5; Mic 1:16; Ezek 5:1; cf. Job 1:20). Indeed, tearing out

one’s hair or beard could indicate shame and anger (Ezra 9:3).” [Douglas R.

Edwards, “Dress and Ornamentation,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New

York: Doubleday, 1992), 234.]

"But

was Elisha an old man short on patience and a sense of humor? This charge is

also distorted, for Elisha can hardly have been more than twenty-five when this

incident happened. He lived nearly sixty years after this..." [HSOBX]

To me, the core meaning of the root carries the day:

קרח 5 vb. make

bald—Qal …—make bald, make a bald patch, shave,

prohibited by law (Lv 21:5), in mourning (Mc

1:16)…”[ David J. A. Clines, ed., The

Dictionary of Classical Hebrew (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic

Press; Sheffield Phoenix Press, 1993–2011), 321.

I can easily

visualize Elisha’s grief over Elijah’s ascension, as portrayed in his ‘My

father, my father’ exclamation at that event.

“And Elisha saw it (comp. ver. 10). The

condition was fulfilled which Elijah had laid down, and Elisha knew that his

request for a “double portion” of his master’s spirit was granted. And he cried, My father! my father! It

was usual for servants thus to address their masters (ch. 5:13), and younger

men would, out of respect, almost always thus

address an aged prophet (ch. 6:21; 13:14,

etc.). But Elisha probably meant something more than to show respect. He regarded himself as Elijah’s specially

adopted son, and hence had claimed the “double portion” of the firstborn.

That his request was granted showed that the relationship was acknowledged.”

[H. D. M. Spence-Jones, ed., 2 Kings

(The Pulpit Commentary; London; New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1909),

21.]

And I can see

him expressing the same intensity of grief as described in Micah 1:16:

“Make yourselves bald

and cut off your hair, for the children of your delight; make yourselves as

bald as the eagle, for they shall go from you into exile.”

“shave your heads. This was a custom associated with mourning the dead. The symbolic

disfigurement was intended to show empathy with those in the throes of grieving

over deceased family members (see Walton, Matthews, and Chavalas 2000:782).” [Richard

D. Patterson and Andrew E. Hill, Cornerstone

Biblical Commentary, Vol 10: Minor Prophets, Hosea–Malachi (Carol Stream,

IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2008), 307.]

“The last

stanza is an address to personified Jerusalem, the city in which Micah stands.

He urges it to engage in full mourning

rites. Behind the prophet’s exhortation must have lain the impulse

of his own aching heart. He has been speaking of places he knew better than

most of his hearers, towns and villages springing from childhood memories. We

recall his poignant reference to “my people” at the end of the former oracle:

how much more would he be affected by the prospect of disaster overtaking his

friends and acquaintances, his own kith and kin? So it is his personal sense of

shock that inspires this appeal to Jerusalem to go into deep mourning. He alludes to the traditional custom of

making a bald patch on the head. Shaving one’s hair, normally worn

long by both sexes, was one of a number of external tokens of sorrow. So

great would be the grief in this case that Micah calls for a larger area than

usual to be shaved.” [Leslie C. Allen, The

Books of Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, and Micah (The New International Commentary

on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1976),

283.

The prohibition of this for priests (Lev 21.5) was understood more as

of the forehead or of ALL the head, not just the back (Deut 14.1), and as being

a special symbol. Leviticus had similar restrictions for the common folk, but

these were very situational: trying to distance from the Canaanite cult of the

dead.

So, at Leviticus 21.5:

“The

prohibition against shaving may be related

to the cult of the dead as a gift of one’s vitality (Milgrom, Leviticus 17–22, 1802), or more likely,

it is one of several mourning rituals in which the person separates from the

community and identifies with the dead (Olyan, 616–17)” [Richard S. Hess,

“Leviticus,” in The Expositor’s Bible

Commentary: Genesis–Leviticus (Revised Edition) (ed. Tremper Longman III

and David E. Garland; vol. 1; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008), 1768.

But

expressions of grief in many/most cases do not carry the connotations of

participating in the cult of the dead—even if the manifestations or symbols are

similar.

Indeed, YHWH

calls for expressions of grief on occasions:

“In that

day the Lord GOD of hosts called for weeping and mourning, for baldness and wearing sackcloth; [Is

22.12)

“And on

that day,” declares the Lord GOD, “I will make the sun go down at noon and

darken the earth in broad daylight. I will turn your feasts into mourning and

all your songs into lamentation; I will bring sackcloth on every waist and baldness on every head; I will make it

like the mourning for an only son and the end of it like a bitter day.” [Amos

8.9-11)

Summary:

There is very

little certainty on the meaning of this saying, as well as on its intended

purpose.

The most

plausible scenario to me looks like this:

·

Elisha expressed his grief over the loss of his ‘adopted father’ in the

way an everyday citizen would have – shaving part of the back of the head.

·

He would have temporarily avoided headgear (if he wore it routinely)

out of the need for public display of his grief/mourning for Elijah.

·

The group of lowest-level employees from the city either passed through

the woods or walked by Elisha (and his party) on the road.

·

They have been scorning him during the entire time, with specific

verbal content not described in the text (like the content of the curse won’t

be).

·

They then turn around in the road, spot Elisha’s shaved spot, and utter

what would have been considered (in that culture for sure) a horrific

violation of social values. Their making fun of a mourner is shocking, and

could easily be the ‘straw that broke the camel’s back’ for Elisha.

·

On top of violating messenger protocols and arrogant rejection of YHWH’s

authority as suzerain – in the ‘scorn’ action—they violate basic rules of

civility and community solidarity.